Could it happen in this age of greed? A leading international musician pays his own way to travel thousands of miles to celebrate the independence of an African nation. He spends a night in a rundown hotel; smokes marijuana with farmers; survives teargas and writes a song that goes down in history. This was Bob Marley 35 years ago at the birth of Zimbabwe – an African story told by those who were there.

It all started with the impossible dream in Harare. Two Zimbabwean businessmen, nightclub owner Job Kadengu and Gordon Muchanyuka, wanted a big name to serenade the new Zimbabwe at midnight on April 17, 1980. Kadengu and Muchanyuka agreed Bob Marley was their man. The two flew to Kingston, Jamaica, to invite Marley, just weeks before independence day.

“By the time the band arrived, a chartered Boeing 707 was on its way from London to Salisbury with 21 tons of equipment; a full 35,000-watt PA system plus backline equipment,” says Zindi. “It was one of the most extraordinary logistics operations. Mick Cater, from Alec Leslie Entertainment, flew down with the equipment and then set himself the problem of building a stage in time for the celebrations. By Wednesday, when the 12-strong road crew arrived in Zimbabwe, he had six hours in which to construct the stage and find sufficient power for the PA system.”

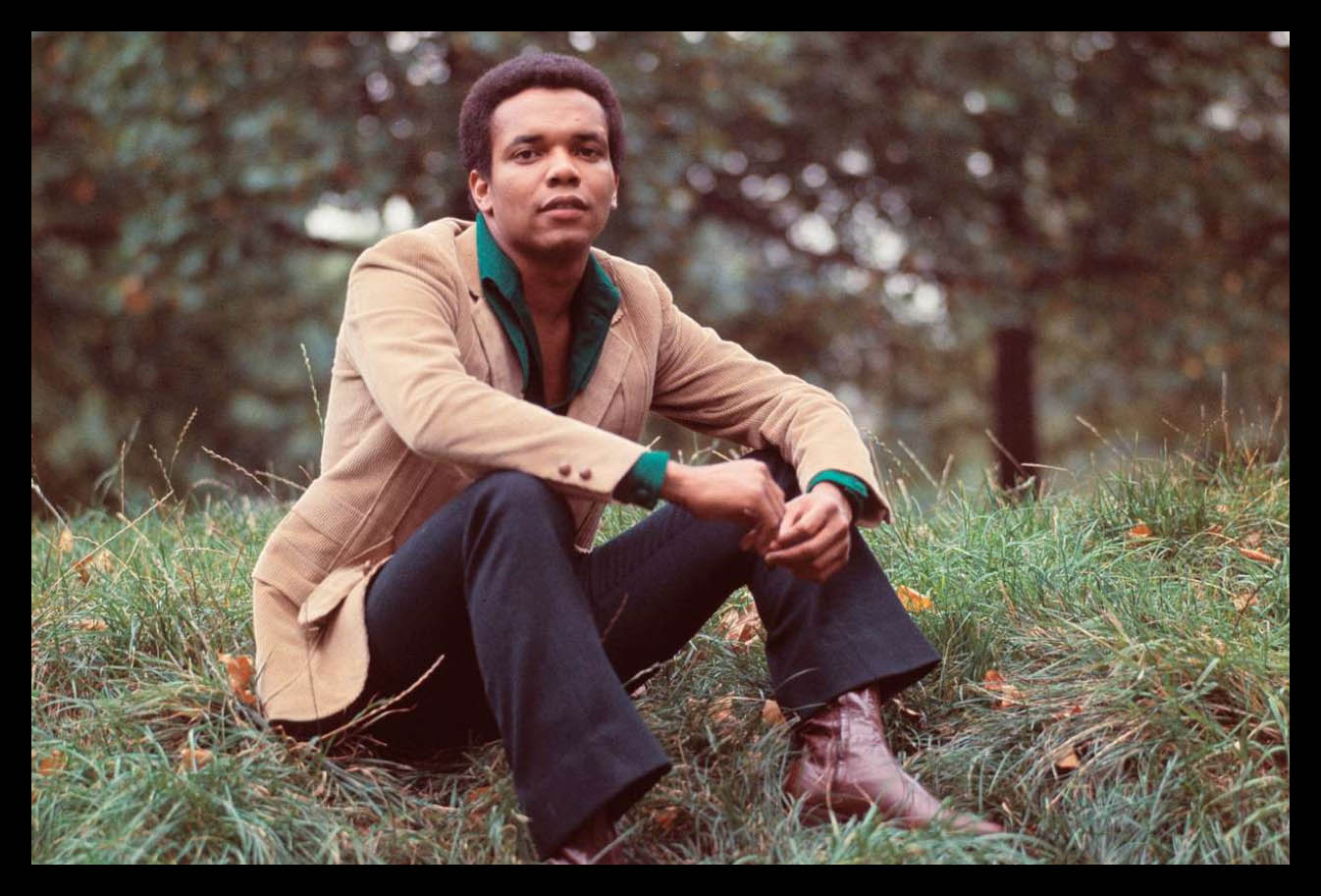

Marley and his crew spent the night, carousing with many former guerrilla fighters, at the run-down Skyline Hotel on the outskirts of Harare as foreign journalists had booked all the big hotels. The next day, Marley traveled to spend time with marijuana farmers in Mutoko, a town 143 kilometers outside Harare, where he sampled the herb. In the last hours of Rhodesia, on April 17, thousands flocked to Rufaro stadium in Mbare, the Harare township that was the crucible of the struggle.

Independence Day - Zimbabwe, 1980

There was a carnival atmosphere; people wore caps and t-shirts bearing the face of the new prime minister, Robert Mugabe. At midnight, the green, gold and black flag of Zimbabwe, with the African fish eagle, replaced the Union Flag. A 32-year-old Prince Charles stood and saluted as the Union Flag came down for the last time in Africa.

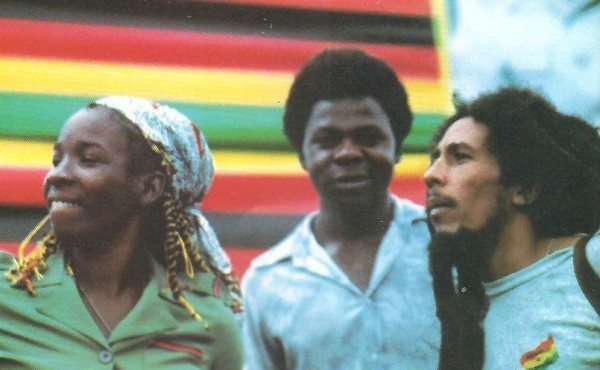

People crushed into the stadium as Marley took to the stage. The police panicked and fired teargas into the crowd. Back-up singers Marcia Griffiths and Rita Marley, the wife of the lead singer, were the first band members to get a whiff of teargas and they ran backstage. When it cleared, they went back. “Bob was still in his element, he didn’t realize what was happening around him,” said Rita in a documentary years later. “So when we got back on stage, this is what Bob said to us: ‘Now I know who the true revolutionary is.’”

“It was a poignant moment; Bob Marley takes a celebratory stance at the front stage, calling out ‘Viva Zimbabwe!’ Each time eliciting a greater response from the audience,” says Zindi. “It is a moment pregnant with possibilities. Rastafari in our father’s land. A realization of the inherent unity in black culture, as emotional for the audience as it is for the band. Homecoming.”

“Bob Marley was at his height and that alone attracted a lot people’s attention to Zimbabwe,” says Gutto. “It was an historic moment of the liberation of Zimbabwe where the white arrogant people declared independence and so on. It was a moment when I and the other progressive intellectuals went to Zimbabwe. It was a special period. It captured the imagination of the world. You can’t hold Marley responsible for what Robert Mugabe did after that.”

When Bob Marley serenaded Zimbabweans celebrating independence

Farai Matiashe – Al Jazeera – Friday, April 17, 2020

Harare, Zimbabwe – Forty years ago, Bob Marley and his band, the Wailers, stepped onto the stage at Rufaro Stadium in Harare to help usher in Zimbabwe’s independence from British and local white minority rule.

It was electrifying. The unmistakable reggae thump of the legendary Jamaican musician filled the air as chants of “Viva Zimbabwe” boomed out over the crowd in-between songs.

“It was a moment I fully savoured,” Christopher Mutsvangwa, one of the fighters during the liberation struggle, known as Second Chimurenga (1966-1979), told Al Jazeera.

“Tears of pain-filled delight rolled down my cheeks,” he recalled of the momentous occasion. “Unfortunately, many of my beloved comrades were not there any more to watch the spectacle they paid the ultimate price of life for.”

That night in April 1980, Zimbabwe became Africa’s newest independent country as Britain’s Union flag was brought down to be replaced by the banner of the nascent state of Zimbabwe.

Months earlier, in December 1979, an agreement signed at London’s Lancaster House had paved the way for the country’s first free elections in February 1980. ZANU-PF, one of the liberation movement parties, won a landslide victory, with its leader, Robert Mugabe, becoming Zimbabwe’s first prime minister.

Marley, one of the most politically and socially influential musicians of his time who also had a strong connection with Africa, was invited to perform during the ceremony celebrating majority rule and internationally-recognised independence for Zimbabwe.

The reggae superstar not only accepted the invitation but also spent tens of thousands of dollars to fly in his band and its equipment to take part in the festivities that started on the evening of April 17.

“That night, Marley and the Wailers expressed solidarity with Zimbabwe,” said Fred Zindi, 22 at the time and now a professor in the Education Department of the University of Zimbabwe.

“It was almost inevitable that a man so identified with the struggles against class and racial oppression should be invited to perform at the celebrations of the birth of a new nation, Zimbabwe,” added Zindi, who had attended the show.

Also among the 40,000-crowd at Rufaro Stadium were heads of government and dignitaries from around the world, including Prince Charles, the heir to the British throne, and then-Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

While the band was playing inside the stadium, largely in front of people invited to attend the occasion, big crowds locked outside tried to enter the packed stadium. Police responded by firing tear gas but Marley remained on stage and the show went on.

Thankfully for many unable to be at the concert on the 17th, Marley agreed to perform again the next day, with an estimated 100,000 people in attendance.

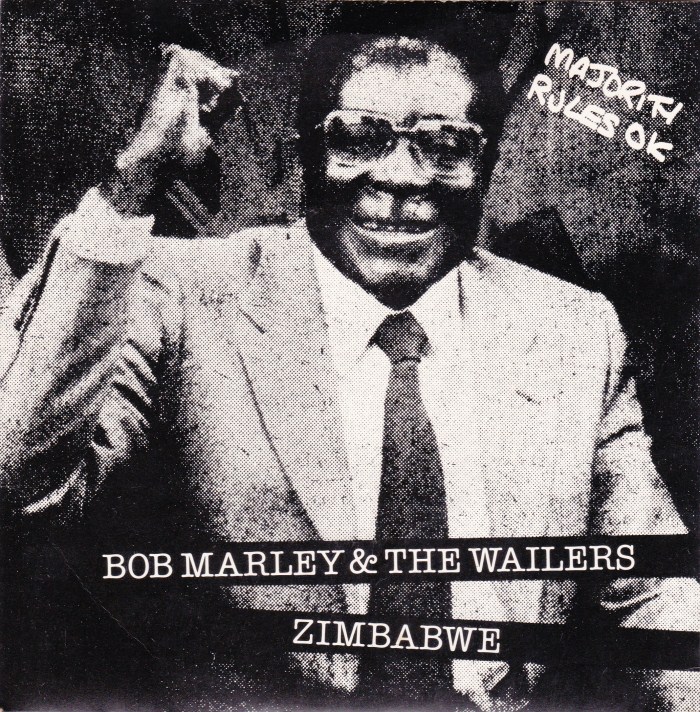

Among the highlights of Marley’s Harare showing was Zimbabwe, a song from his 1979 Survival album. In it, Marley sings: “Every man gotta right to decide his own destiny/And in this judgement there is no partiality/So arm in arms, with arms, we’ll fight this little struggle/’Cause that’s the only way we can overcome our little trouble/ Brother, you’re right, you’re right, you’re right, you’re right, you’re so right/We gonna fight, we’ll have to fight, We gonna fight, fight for our rights.”

The song, an anthem for Zimbabwe’s freedom, took shape during one of the Rastafarian musician’s visits to Addis Ababa in 1978, according to Gibson Mandishona, a Zimbabwean statistician working at the time for the United Nations in Ethiopia.

“Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia had given a vast piece of land to Rastafarians from Jamaica, to enable them to lead their dedicated lifestyle. Marley used to support and enjoy by being with the Rastafarians, and thus paid bi-annual visits to Addis Ababa,” Mandishona told Al Jazeera.

“In one of his visits in 1978, a friend told me that Marley was asking about me and the UN jazz band of which I was leading. This was a leisure music band of some nine UN experts which played as hobby at social functions.”

Mandishona said when he met Marley, the international superstar told him: “I can smell Zimbabwe becoming independent soon.”

Mandishona continued: “He began sounding the Zimbabwe tune he had been experimenting on. It was typically a reggae total format. Being a Shona poet, I moderated the tune to have some Shona rhythm bits.”

Marley died of cancer in 1981 at the age of 36 but his music still lives on worldwide, including throughout Africa – in Zimbabwe, several local reggae groups have over the years played concerts in Marley’s honour.

“Through his music, he was fighting capitalism and oppression of the Black [people] by colonialists,” said Victor Matemadanda, secretary-general of the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans’ Association and also the country’s deputy defence minister. “Himself being a product of slave trade, he connected much with his songs,” added Matemadanda, stressing Marley’s struggle for a united and free Africa.

Mutsvangwa echoed the same view, highlighting the role of Marley’s music in Zimbabwe’s liberation movement.

“The timely arrival of Marley’s reggae music and its globalist Pan-African message changed political attitudes as the young freedom fighters marched to war,” said Mutsvangwa, a former diplomat. Marley’s music, along with that of Zimbabwean superstar Thomas Mapfumo, had become the battle cry of freedom fighters, added Mutsvangwa.

Professor Nhamo Anthony Mhiripiri, a chairperson in the Media and Society Studies department at Midlands State University, described Marley’s music as”politically committed”.

“He was an organic thinker who participated in the struggles … against colonialism. Zimbabwe was a highly mediatised hotspot where many atrocities were committed and publicised. Marley played his part through highlighting the suffering of Zimbabweans and their aspirations for self-liberation.”

Forty years on, the independence anniversary on Saturday will be a low-key affair that will find Zimbabweans, the majority of whom struggle with a deepening economic crisis, under lockdown as the country tries to curb the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

As of April 17, Zimbabwe had 24 confirmed cases, including three deaths.