I Can See Clearly Now!

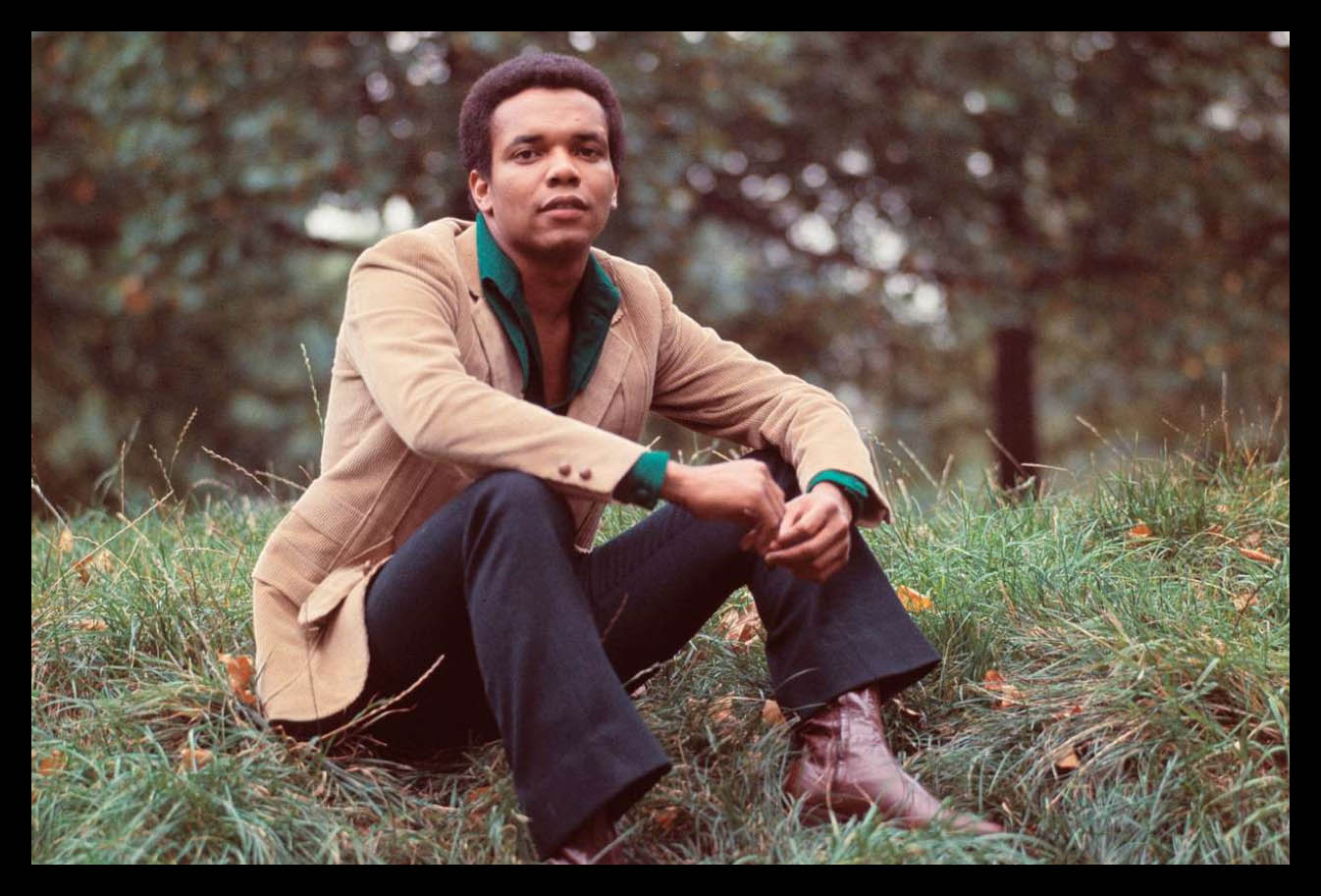

Johnny Nash, a singer-songwriter, actor and producer who rose from pop crooner to early reggae star to the creator and performer of the million-selling anthem “I Can See Clearly Now,” died Tuesday, his son said.

Nash, who had been in declining health, died of natural causes at home in Houston, the city of his birth, his son, Johnny Nash Jr., told The Associated Press. He was 80.

Nash was in his early 30s when “I Can See Clearly Now” topped the charts in 1972 and he had lived several show business lives. In the mid-1950s, he was a teenager covering “Darn That Dream” and other standards, his light tenor likened to the voice of Johnny Mathis. A decade later, he was co-running a record company, had become a rare American-born singer of reggae and helped launch the career of his friend Bob Marley.

Nash praised “the vibes of this little island” when speaking of Jamaica, and he was among the first artists to bring reggae to U.S. audiences. He peaked commercially in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he had hits with “Hold Me Tight,” “You Got Soul,” an early version of Marley’s “Stir It Up” and “I Can See Clearly Now,” still his signature song.

Reportedly written by Nash while recovering from cataract surgery, “I Can See Clearly Now” was a story of overcoming hard times that itself raised the spirits of countless listeners, with its swelling pop-reggae groove, promise of a “bright, bright sunshiny day” and Nash’s gospel-styled exclamation midway, “Look straight ahead, nothing but blue skies!”, a backing chorus lifting the words into the heavens.

The rock critic Robert Christgau would call the song, which Nash also produced, “2 minutes and 48 seconds of undiluted inspiration.”

He charted 11 hits on the Billboard Hot 100, including a pair of top 10s: “Hold Me Tight” in 1968 and the No. 1 “I Can See Clearly Now” in 1972. The latter spent four weeks atop the list. “Clearly” also led the Adult Contemporary Songs airplay chart for a month. He also claimed nine hits on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, one of which reached the top 10: “Let’s Move & Groove (Together),” a No. 9-peaking hit in 1965.

Penned by Nash, “I Can See Clearly Now” also was a top 40 hit on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart for Ray Charles in 1978. It surged back to the charts in 1993 thanks to a cover by Jimmy Cliff for the film Cool Runnings. In 1994, Cliff’s rendition hit No. 18 on the Hot 100 and No. 9 on the Adult Contemporary chart.

Although overlooked by Grammys judges, “I Can See Clearly Now” was covered by artists ranging from Ray Charles and Donny Osmond to Soul Asylum and Jimmy Cliff, whose version was featured in the 1993 movie “Cool Runnings.” It also turned up everywhere from “Thelma and Louise” to a Windex commercial, and in recent years was often referred to on websites about cataract procedures.

“I feel that music is universal. Music is for the ears and not the age,” Nash told Cameron Crowe, then writing for Zoo World Magazine, in 1973. “There are some people who say that they hate music. I’ve run into a few, but I’m not sure I believe them.”

The fame of “I Can See Clearly Now” outlasted Nash’s own. He rarely made the charts in the years following, even as he released such albums as “Tears On My Pillow” and “Celebrate Life,” and by the 1990s had essentially left the business. His last album, “Here Again,” came out in 1986, although in recent years he was reportedly digitizing his old work, some of which was lost in a 2008 fire at Universal Studios in Los Angeles.

Nash was married three times, and had two children. He had loved riding horses since childhood and as an adult lived with his family on a ranch in Houston, where for years he also managed rodeo shows at the Johnny Nash Indoor Arena.

In addition to his son, he is survived by daughter Monica and wife Carli Nash.

John Lester Nash Jr., whose father was a chauffeur, grew up singing in church and by age 13 had his own show on Houston television. Within a few years, he had a national following through his appearances on “The Arthur Godfrey Show,” his hit cover of Doris Day’s “A Very Special Love” and a collaboration with peers Paul Anka and George Hamilton IV on the wholesome “The Teen Commandments (of Love).” He also had roles in the films “Take a Giant Step,” in which he starred as a high school student rebelling against how the Civil War is taught, and “Key Witness,” a crime drama starring Dennis Hopper and Jeffrey Hunter.

His career faded during the first half of the 1960s, but he found a new sound, and renewed success, in the mid-60s after having a rhythm and blues hit with “Let’s Move and Groove Together” and meeting Marley and fellow Wailers Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston during a visit to Jamaica. Over the next few years their careers would be closely aligned.

Nash convinced his manager and business partner Danny Sims, with whom he formed JAD Records, to sign up Marley and the Wailers, who recorded “Reggae On Broadway” and dozens of other songs for JAD. Nash brought Marley to London in the early 1970s when Nash was the bigger star internationally and with Marley gave an impromptu concert at a local boys school. Nash’s covers of “Stir It Up” and “Guava Jelly” helped expose Marley’s writing to a general audience. The two also collaborated on the ballad “You Poured Sugar On Me,” which appeared on the “I Can See Clearly Now” album.

After the 1980s, Nash became a mystery to fans and former colleagues as he stopped recording and performing and rarely spoke to the press or anyone in the music industry. In 1973, he told Crowe that he anticipated years of hard work: “What I want to do is be a part of this business and to express myself and get some kind of acceptance by making people happy.”

A quarter century later, he explained to The Gleaner during a visit to Jamaica that it was “difficult to develop major music projects” without touring and promoting and that he preferred to be with his family.

“I think I’ve achieved gratification in terms of the people I’ve had the chance to meet. I never won the Grammy, but I don’t put my faith in things of that nature,” he added. “A lifetime body of work I can be proud of is more important to me. And the special folksy blend to the music I make, that’s what it is all about.”

Additional reporting by Keith Caulfield.