The Bob Marley Story – Part One

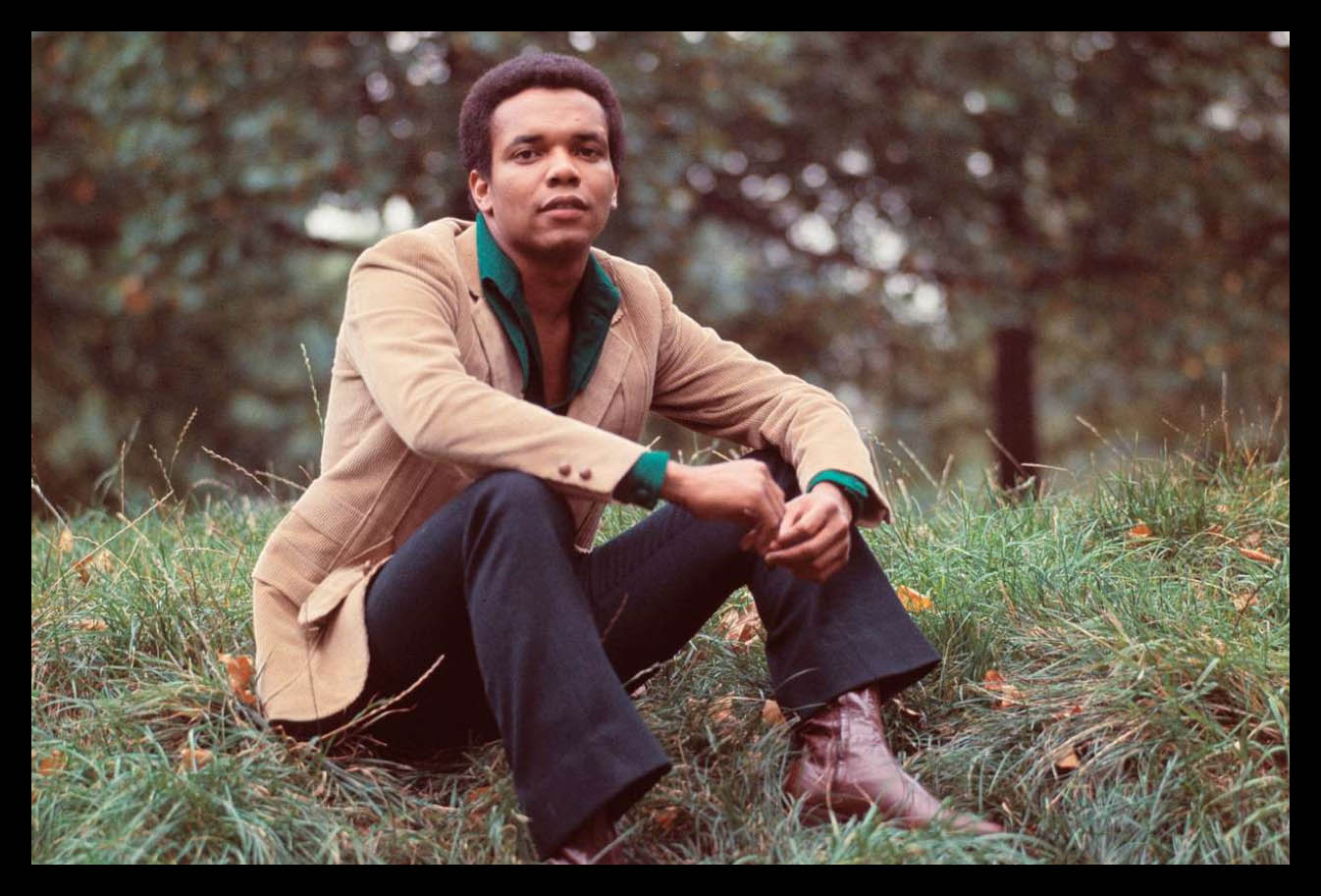

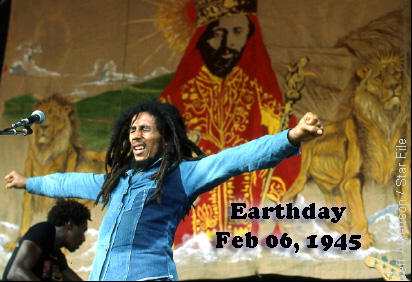

Robert Nesta Marley was born February 6, 1945 in rural St. Ann’s Parish, Jamaica; the son of a middle-aged white, British military officer father and a local teenaged black mother. Bob had little exposure to his father but got loving care from his mother Cedella and his Grandfather who was known as an obeah man… a kind of shaman or medicine man who had considerable influence on the young Bob. At age 14, he left home to pursue a music career in Kingston, becoming a pupil of local singer and devout Rastafarian Joe Higgs.

He began recording in 1962, debuting on a ska-tempoed song called “Judge Not”. Looking back, it seems very fitting that the song’s lyrics were firmly routed in a moral and social dimension. He formed a vocal trio with some childhood friends, Neville “Bunny” Livingston (later Bunny Wailer) and Peter McIntosh (later Peter Tosh). They took the name the Wailers because they were ghetto sufferers who’d been born “wailing.” As practicing Rastas, they grew their hair in dreadlocks and smoked ganja, believing it to be a sacred herb that brought enlightenment.

1973’s Catch a Fire, the Wailers’ Island debut, was the first of their albums released outside of Jamaica, and immediately earned worldwide acclaim; the follow-up, Burnin’, launched the track “I Shot the Sheriff, ” a Top Ten hit for Eric Clapton in 1974. With the Wailers poised for stardom, however, both Bunny Livingstone and Peter Tosh quit the group to pursue solo careers; Bob then brought in the I-Threes, which in addition to Rita Marley consisted of singers Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt. The new line-up proceeded to tour the world prior to releasing their 1975 breakthrough album Natty Dread, scoring their first UK Top 40 hit with the classic “No Woman, No Cry.” Sellout shows at the London Lyceum, where Marley played to racially-mixed crowds, yielded the superb Live! later that year, and with the success of 1976’s Rastaman Vibration, which hit the Top Ten in the U.S., it became increasingly clear that his music had carved its own niche within the pop mainstream.

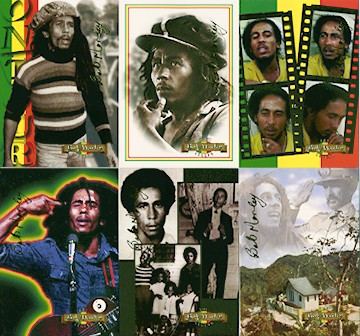

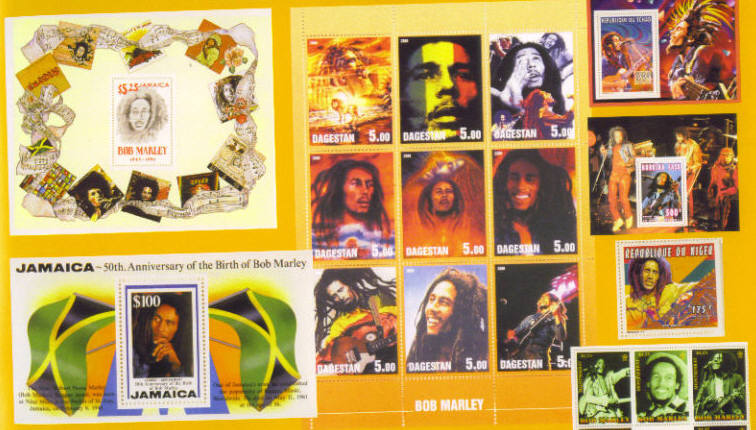

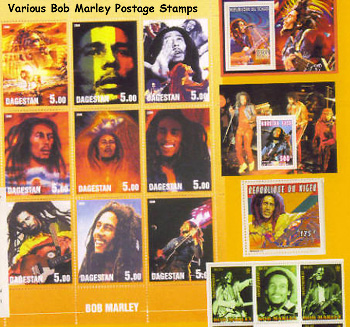

Bob Marley’s musical impact and spiritual message spreads around the globe and continues to expand. In his homeland of Jamaica he is a National Hero and the government that is often very tough on the youth and the rastas and even feared the power of Marley, have honored his life and works with two Jamaican postage stamps. Not only was Marley a key figure in maintaining peace in his homeland at several crucial times during his life, he also has been as important as the country’s largest banks and corporations in supporting Jamaica’s position in the world economic community. Robert Nesta Marley’s life and works continue to spread the joy of the riddum and life, the message of inity and overstanding and a continually blossoming prosperity.

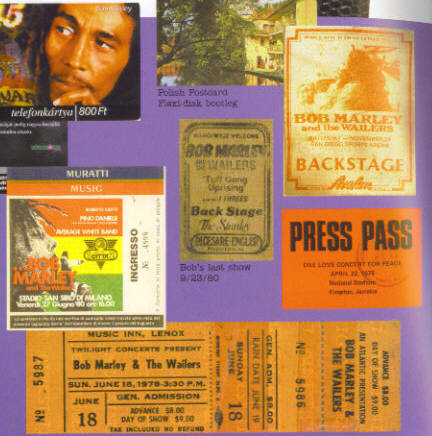

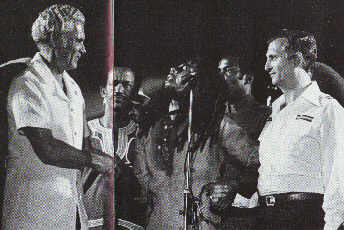

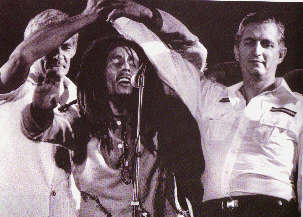

Bob Marley unites JA at the One Love Concert, April 22, 1978 in Kingston, Jamaica

So influential a cultural icon had Marley become on his home island by mid-decade that Time magazine exclaimed, “He rivals the government as a political force.” On December 3, 1976, Marley was scheduled to give a free “Smile Jamaica” concert, aimed at reducing tensions between warring political factions. A couple of days before the show, he and his entourage were attacked by gunman. Wounded but not killed, Marley electrified a crowd of 80,000 people when he took the stage that night – a gesture of survival that only heightened his legend. Two years later he symbolically united the nation by bringing the rival political party leaders together on stage at the One Love Concert with Marley, Jacob Miller, Peter Tosh and more…

Bob even has a series of three Marvel Comic books celebrating his life – IRON (this issue), LION (issue #2), ZION (issue #3).

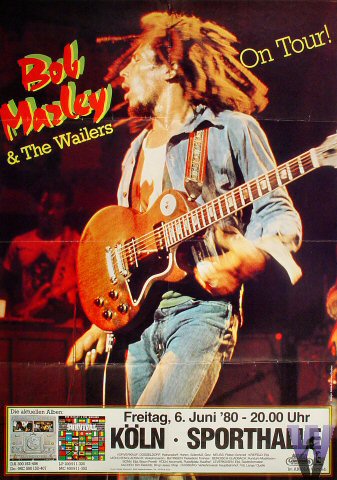

1980 loomed as Marley’s biggest year yet, kicked off by a concert in the newly-liberated Zimbabwe; a tour of the U.S. was announced, but while jogging in New York’s Central Park he collapsed, and it was discovered he suffered from cancer which had spread to his brain, lungs and liver. Uprising was the final album released in Marley’s lifetime — he died May 11, 1981 at age 36.

At the state funeral there were readings from the Bible by Jamaica’s Governor General, and by Michael Manley, the Leader of the Opposition Party. Edward Seaga, the Prime Minister, eulogized The Honorable Robert Nesta Marley.

The Wailers, with the I-Threes backing them up on vocals, performed some of Bob’s songs. The Melody Makers, a group consisting of four of Bob and Rita Marley’s children, led by their eldest son Ziggy, also performed in his honor. His mother, Mrs. Cedella Booker, sang “Coming In From the Cold”, one of the last songs Bob wrote.

Bob Marley and the Wailers – Catch A Fire This documentary, Bob Marley and the Wailers: Catch a Fire, returns to Dynamic Studios in Kingston, Jamaica, shedding light on the development of the album, the thought process of Bob, Peter, and Bunny, and the importance of the music on a song-by-song basis. The story of Catch a Fire is presented through interviews with the band members, studio musicians, and former head of Island Records Chris Blackwell. Throughout are raw studio rehearsal footage, BBC TV footage, and home movies that include performances of “Concrete Jungle,” “Slave Driver,” “Stir It Up,” and “Stop That Train.” The documentary wraps up with rare black-and-white footage of the Wailers’ tour in Edmonton, London, in 1973 with an electrifying performance of the Burnin’ song “Get Up, Stand Up.”

Old pirates yes they rob I

Sold I to the merchant ships

Minutes after they took I from the

Bottomless pit

But my hand was made strong

By the hand of the almighty

We forward in this generation triumphantly

All I ever had is songs of freedom

Won’t you help to sing these songs of freedom

“Cause all I ever had redemption songs,

redemption songs

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery

None but ourselves can free our minds

Have no fear for atomic energy

“Cause none a them can stop the time

How long shall they kill our prophets

While we stand aside and look

Some say it’s just a part of it

We’ve got to fulfill the book

Won’t you help to sing another song of freedom

‘Cause all I ever had, redemption songs

All I ever had, redemption songs

These songs of freedom, songs of freedom.

by Robert Nesta Marley

A song that says so much about Bob and his music, it was one of the last songs he was ever to play in concert… after an amazing show at NYC’s Madison Square Garden, he had collapsed while jogging in Central Park the next morning. Rita Marley and some of the band had wanted to stop the tour but Bob wanted to continue… none the less, the next show on September 23, 1980 would be Bob’s final concert. It took place at the Stanley Theater, Pittsburg, Pa., USA – the recording of “Redemption Song” from that night can be heard on the “Songs of Freedom” Box Set

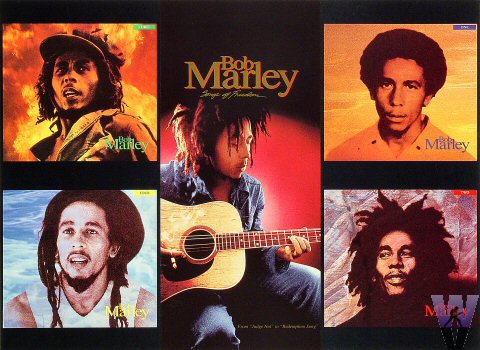

BIG News if you missed getting the initial release… The 4-CD’s compiled for Island Records Bob Marley “Songs of Freedom” Limited Edition Box Set (one million copies) has just been re-issued due to overwhelming demand

Nine Mile, situated high in the mountains of Jamaica, is located in the midst of a vast magical and beautiful part of the island that remains greatly untouched by the modern world and the thriving tourist industry of the island. It is a small village in the parish of St. Ann. Nine Mile was his birthplace and this small house (pictured below) is the final resting place of the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley.

Wailers John Peel BBC Broadcast

John Robert Parker Ravenscroft, OBE (30 August 1939 – 25 October 2004), known professionally as John Peel, was an English disc jockey, radio presenter, record producer and journalist. He was the longest serving of the original BBC Radio 1 DJs, broadcasting regularly from 1967 until his death in 2004.

Beacon Theater - 04-30-1976

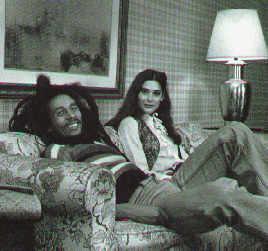

Bob and Cindy Breakspeare at the Essex House, NYC

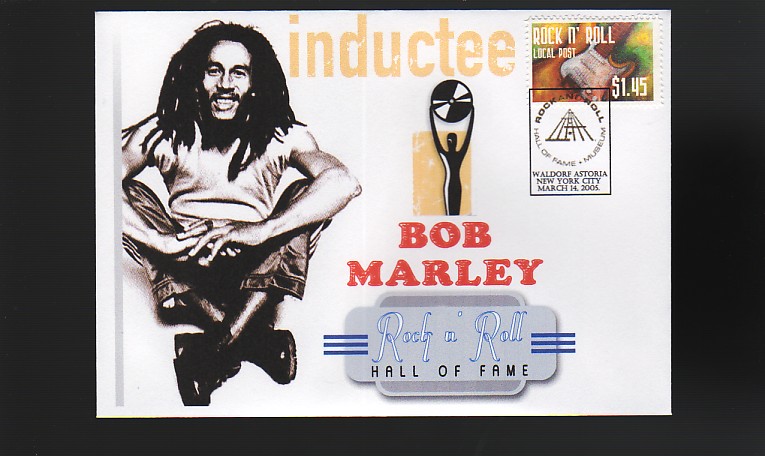

Bono’s (U2) Bob Marley Induction Speech to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

“I know claiming Bob Marley as Irish might be a little difficult, but bear with me. Jamaica and Ireland have lots in common – Chris Blackwell, weeds, lots of green weeds – religion – the philosophy of procrastination (don’t put off till tomorrow what you can put off till the day after), unless of course its freedom.

We are both islands, we are both colonies, we share a common yoke – the struggle for identity, the struggle for independence. The vulnerable and uncertain future that is left behind when the jack boot of the Empire has finally retreated – roots – the getting up, the standing up – and the hard bit, the staying up – in such as struggle, and often violent struggle, the voice of Bob Marley was a voice of reason; one love, ONE LOVE! So when I first heard Bob Marley, I not only felt it, I felt I understood it.

It was 1976; in Dublin we were listening to punk. It was the Clash and Eric Clapton’s cover of “I Shot the Sheriff” that brought him home to us. Bob Marley and the Wailers had love songs you could admit listening to, songs of hurt – hard but healing.

Tuff Gong.

Politics without rhetoric.

Songs of freedom where that word meant something again. New hymns to a dancing God, redemption songs, a sexy revolution where Jah is Jehovah on a street level, not over his people. Not just stylin – Jammin – The Lion of Judah down the line of Judah from Ethiopia, were all began for Rastaman. Were everything began – well maybe.

I spent some time Ethiopia with my wife Ali and everywhere we went, we saw Bob Marley’s face – bonal, wise. Solomon and the Queen of Sheba on every street corner; there he was dressed to hustle God. “Let my people go”, an ancient plea – Prayers catching fire in Mozambique, Nigeria, Lebanon, Alabama, Detroit, New York, Notting Hill, Belfast – Doctor King in dreads, a third and first world superstar.

Meant to slavery and were imagination begins.

He was the new music rocking out of the shanty towns born from calypso and raised on the chilled out R&B beamed in from New Orleans – lolling lopping rhythms – telling it like it was, like it is, like it shall be – skanking.

Ska, bluebeat, rock steady, reggae dub and now ragga, and all of this from a man who drove three BMWs! BMW?! Bob Marley and the Wailers!

Rock-and-roll loves its juvenilia, its caricatures, its cartoons, the protest singer, the gospel singer, the pop star, the sex god, your more mature messiah types. We love the extremes and we – re expected to choose… the mud of the blues or the oxygen of the gospel, it hellbound on our trail or the band of angels. Marley didn’t choose. Marley didn’t walk down the middle, he raced to the edges, embracing all extremes and creating a oneness. His oneness; One Love.

He wanted everything at the same time and was everything at the same time: prophet, sole rebel, Rastaman, herbsman, wild man, a natural mystic man, ladies man, island man, family man, Rita’s man, soccer man, showman, shaman, human, JAMAICAN!”

Bono’s (U2) Bob Marley Induction Speech to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Bob Marley chronology 1945-1981 by Roger Steffens

1945

Nesta Robert Marley is born in a tiny hilltop settlement called Nine Miles, in the parish of St. Ann in northern Jamaica at 2:30 in the morning of February 6. His father is in his 50s, a white Jamaican named Norval Marley. His mother is the 19-year-old Cedella Malcolm. Although they are married, the couple never lives together because of the disapproval of “Captain” Marley’s family, which threatens to disown him.

1948

At the age of three, Bob is reported by the locals to have psychic powers. He reads the hands of several people in the area, revealing to them surprisingly intimate knowledge of their lives.

1950

Norval sends for his son to come to Kingston, where he promises to educate him. Reluctant but hopeful, Cedella sends Bob alone to Kingston on a mini-bus, where his father meets him. Instead of school, Bob is sent to live with an infirm and elderly lady, and never sees his father again. It will be almost 18 months before his mother discovers his whereabouts and comes to the capital to bring him back to Nine Miles.

1951

Upon his return to St. Ann’s, Bob is asked once again to read the hand of one of his mother’s adult friends. He refuses, announcing, “I’m a singer now.”

1956

Around this time, Toddy Livingstone and his son Bunny move to Nine Mile. The 11-year-old Marley strikes up a fast friendship, strengthened as Bob’s mother moves in with Bunny’s father. Eventually, the new “family” moves together to Kingston.

1962

Bob Marley, 16 years old, cuts his first recordings for Leslie Kong’s Beverly’s label. His initial single contains a pair of self-composed tracks called “Judge Not” and “Do You Still Love Me.” His second is a cover of Claude Grey’s 1961 U.S. country & western hit “One Cup of Coffee,” released under the Kong-imposed pseudonym of Bobby Martell. An additional track, “Terror,” is recorded but never released. Both records fail with the public, and Bob returns for coaching to the tenement yard of successful Trench Town singer Joe Higgs, who has been tutoring him. There he teams with the young man with whom he has been raised as a brother, Bunny Wailer, along with Peter Tosh, Junior Braithwaite, with occasional contributions from young women named Beverly Kelso and Cherry Green.

1963

1963

By December of 1963, Higgs declares the newly named “Wailers” ready to audition forth

1964

Recording with the legendary Skatalites as their backing band, the Wailers release an almost monthly stream of records, including Peter Tosh’s first lead vocals “Hoot Nanny Hoot” and “Maga Dog.” They cover Jimmy Clanton’s “Go Jimmy Go” and Dion and the Belmonts’ “Teenager in Love.” Spirituals that year include “Amen,” “Habits,” and “Wings of a Dove.” First recordings appear of their classics “It Hurts To Be Alone” with Junior Braithwaite’s haunting lead, and “There She Goes.” Bob assists Coxson by auditioning and coaching new singers, including a group called the Soulettes. Rita Anderson of that trio pairs with Bob on a duet called “Oh My Darling.” They make occasional stage show appearances, but concentrate primarily on daily rehearsals to polish their sound, influenced in particular by the harmonic style of the Impressions. They also record backup vocals for Barbadian superstar Jackie Opel and local youth Delroy Wilson. Junior Braithwaite leaves for America.

1965

Beverly Kelso quits because of Marley’s unrelenting urge for perfection, even in rehearsals. The Wailers are now down to their core trio of Bunny, Bob and Peter. First recordings are made of “One Love,” “Rude Boy,” “I’m Still Waiting,” “I’m Gonna Put It On,” and “Cry to Me.” They also sing backup to Jackie Opel again, as well as Lee Perry and Leonard “The Ethiopian” Dillon. Cover versions are released of the Beatles’ “And I Love Her,” Tom Jones’ “What’s New Pussycat,” and Irving Berlin’s standard, “White Christmas.” By the end of the year, the Wailers have five tunes in the top ten at the same time, but Coxson gives them a “bonus” of just £99 for all their hits.

1966

Disgusted at the lack of financial rewards after two years of constant hit-making, the Wailers decide to start their own label. On February 10, Bob marries Rita Anderson, and leaves the following day for his mother’s home in Wilmington, Delaware. There he gets a job on the night shift of a Chrysler automobile factory, working in the parts department. He is replaced in the group by Constantine “Dream” “Vision” Walker of the Soulettes, who is Rita’s cousin. Bunny, Peter and Dream, sometimes joined by Rita, record “Who Feels It Knows It,” “Let Him Go,” “Don’t Look Back,” “Dancing Shoes,” and “I Stand Predominate.” They become known as the prime defenders of the “rude boys,” or as Bunny calls them, the “roots radicals.” Haile Selassie I, the God of the Rastafarians, arrives in Jamaica on April 21, and the Wailers embrace the faith, beginning to grow their locks, and to take instruction from elder dreads in their community. When Bob returns in October, he too “sights” Rasta. Armed now with enough money to found their own label, they call it Wail ‘n Soul ‘m, and release their first independent single, a cry of emancipation from Coxson called “Freedom Time” backed with “Bend Down Low.” “Nice Time,” “Hypocrites,” “Mellow Mood,” “Thank You Lord,” and “Stir It Up” are all recorded before the end of the year.

1967

A year of building and regrouping, during which time the Wailers open a tiny shop in Kingston. Bob delivers Wail ‘n Soul ‘m records around the island by bicycle. Bunny is put in jail from June 1967 until September 1968 on falsified ganja charges. Peter records “Funeral” and “Hammer.” Bob sings the prophetic “Pound Get a Blow” and shortly after, the Pound is devalued. They have moderate hits with much of their material, but are unable to get ahead enough financially to achieve stability for their label. In parallel career developments, American soul singer Johnny Nash discovers Marley at a Rasta grounation (a gathering to give thanks are praises to Jah). He and his partners Danny Sims and Arthur Jenkins sign Peter and Bob to writing contracts, and the Wailers to performing agreements. Bob tells them that he wants to be a star on the rhythm & blues charts in America, and the JAD label (Johnny, Arthur and Danny) begins recording them in Jamaica, with sweetening done in New York by members of Aretha Franklin’s band. The vast majority of the songs remain in the vaults, unheard to this day.

1968

Sims/Nash continue to groom Bob Marley for international stardom, while the Wailers lay their first versions of later hits like “Don’t Rock My Boat,” and “Soul Rebel.” Peter records “Stepping Razor,” written by mentor Joe Higgs. From 67-69, the Wailers had frequent periods in which they fled the tension-filled confines of Kingston for solace in the hills of Bob’s birth in Nine Miles, in the parish of St. Ann. Here they grow food and live communally, composing songs and regaining touch with the sources of their original inspiration.

1969

In the summer Bob and Rita visit Bob’s mother in Delaware. There, Bob prophesies to a couple of young American friends, Ibis Pitts and Dion Wilson: “I am going to die when I am 36.” On the night before Woodstock, Bob and Ibis stay up all night twisting beads and wires into hippie jewelry to sell at the festival. Bob writes “Comma Comma” which becomes an international hit for Johnny Nash.

During the late 60s Bob also records his rarest song, “Selassie Is The Chapel,” written especially for him by Mortimo Planno. Only 26 copies are pressed, twelve of which are brought to Ethiopia by Bob’s close friend, Jamaican football hero Allan “Skill” Cole.

1970

In the spring, the Wailers agree to record an album for Leslie Kong, Bob’s original producer, who has now become a millionaire from the sales of such songs as “My Boy Lollipop” and “The Israelites.” The Wailers make the world’s first real reggae album (as opposed to a collection of singles) called “The Best of the Wailers,” a set of songs designed as a pep talk to themselves. Bunny urges Kong not to title the album this way, claiming that one never knows one’s best until he is at the end of his life. Since the Wailers are so fit, Bunny reasons, it must mean that the young Kong is at the end of his life. Kong ignores the warning and eventually releases the album with that title. Shortly after, he drops dead. Next the Wailers join with another emigré from Coxson’s studio, the diminutive sprite called Lee “Scratch” Perry. Their time together lasts less than a year, but it produces what many consider the finest trio work of the Wailers’ career, backed by the powerful Upsetters rhythm team of the Barrett Brothers, Aston “Family Man” on bass and Carlton on drums. They record such classics as “Soul Rebel,” “400 Years,” “No Sympathy,” “Kaya,” “Brand New Secondhand,” “Mr. Brown,” Dreamland,” and “African Herbsman.” They agree with Perry that all proceeds from the sales of their records will be split 50-50, an arrangement which Perry negates almost immediately. He sells their tapes to Trojan in England, who release them as the albums “Soul Rebels,” “African Herbsman,” and “Soul Revolution Part II,” but the Wailers never see a penny from any of them (and have not to the present time).

1971

Furious with Perry, the Wailers start another label, Tuff Gong, titled after a nickname Bob has been given among his ghetto brethren, to b

1972

Bunny begins his own Solomonic label, releasing “Search for Love.” Bob is brought to England to back a Johnny Nash tour in which Nash is billed as “the King of Reggae.” During ’71 and ’72, Bob plays more than 400 shows in high schools and colleges throughout Britain. A final Danny Sims-Nash session yields a CBSUK single “Reggae on Broadway.” Sims signs the Wailers to white Jamaican millionaire Chris Blackwell, whose Island records has been re-releasing Jamaican recordings since 1961, including Bob’s early solo work, as well as the initial Wailers records. Blackwell gives Bunny, Bob and Peter £8,000 to record an album, “Catch A Fire,” which they complete in less than a month.

1973

“Catch A Fire” is released in a unique zippo-lighter cover and receives ecstatic reviews which hail it as a masterpiece of the newly sophisticated Caribbean sound. The Wailers play emotional concerts live on the BBC, and open in New York City’s Max’s Kansas City club for Bruce Springsteen. The group records a follow-up album called “Burning” which proves to be the trio’s final release together. During the winter of 72-73, the Wailers reportedly work every day in the UK for three months, either in the studio or in concert, and at the end of that time they each receive £100. Bunny quits the group to pursue a solo career and vows never to return to Babylon. In October, Bob and Peter open an American tour with Sly and the Family Stone, but Sly fires them after five shows because they are not connecting with his audience. By the end of the year, Peter Tosh quits as well, wishing to pursue his own music. The future for the Wailers looks bleak.

1974

A time of regrouping for the band, as Bob keeps the core of the Barrett Brothers rhythm section to back him now as a solo artist under the name Bob Marley and the Wailers. He replaces Peter and Bunny with a trio of female singers who have had successful careers in Jamaica: Marcia Griffiths, Judy Mowatt and Rita Marley. The resulting album “Natty Dread,” is his breakthrough, acclaimed as a militant work of uncompromising revolutionary fervor. Peter starts his own Intel-Diplo H.I.M. (Intelligent Diplomat for His Imperial Majesty) label, releasing “What You Gonna Do,” “Burial,” and “Ketchy Shuby,” among others.

1975

Bob tours internationally, playing a notable series of dates at London’s Lyceum Theatre, which result in the “Live” album. H

1976

“Rastaman Vibration” becomes Bob’s only top-ten album in America, and sells millions of copies worldwide. He plays major European venues, selling out everywhere. By the end of the year, rightly or wrongly, it is felt in Jamaica that Bob’s endorsement of a candidate can actually swing a national election to that person. Bob approaches socialist Prime Minister Michael Manley, offering to perform a free concert for his countrymen, insisting however that the event be free of any political overtones. Manley agrees, setting Sunday, December 5 as the date for a gigantic festival in Kingston’s Heroes Park Circle. But once Bob has accepted, Manley announces that national elections will be held shortly after the event. Bob has been co-opted, and immediately comes under death threats from the opposition party of right-wing candidate Edward Seaga. On Friday night, December 3, several gunmen break into Bob’s compound at S6 Hope Road in Kingston, and shoot Bob, his wife, and Don Taylor, his manager. Two nights later, Bob appears before 80,000 people and plays an emotional set of music, displaying his wounds to the crowd. He then leaves the island for a 14 month exile.

1977

Bob spends much of this year in London, living with the reigning Miss World, Cindy Breakspeare. He records enough material for two albums, “Exodus” and “Kaya,” and prepares to embark on what is planned as the biggest reggae tour in history. Bob performs the European leg, including a filmed concert at London’s Rainbow, but cancels the tour at the end of June when doctors diagnos

1978

Bob is approached by rival gunmen from Jamaica’s two leading political parties, and asked to come home to headline the “One Love Peace Concert.” The event is to be held to cement a truce declared by the warring factions in Kingston’s ghettoes. On April 22, the 12th anniversary of Selassie’s visit to Jamaica, under a full moon, Bob is the final performer in an eight-hour concert at the National Stadium. At its triumphant finale, he calls onstage Prime Minister Manley and his political enemy Edward Seaga and makes them shake hands in front of 100,000 people. For his actions that night, and for his exemplary devotion to world unity and the struggle against oppression, Bob receives the United Nations’ Peace Medal in New York in June, given “on behalf of 500 million Africans.” That summer, his “Kaya” tour sets new attendance records.

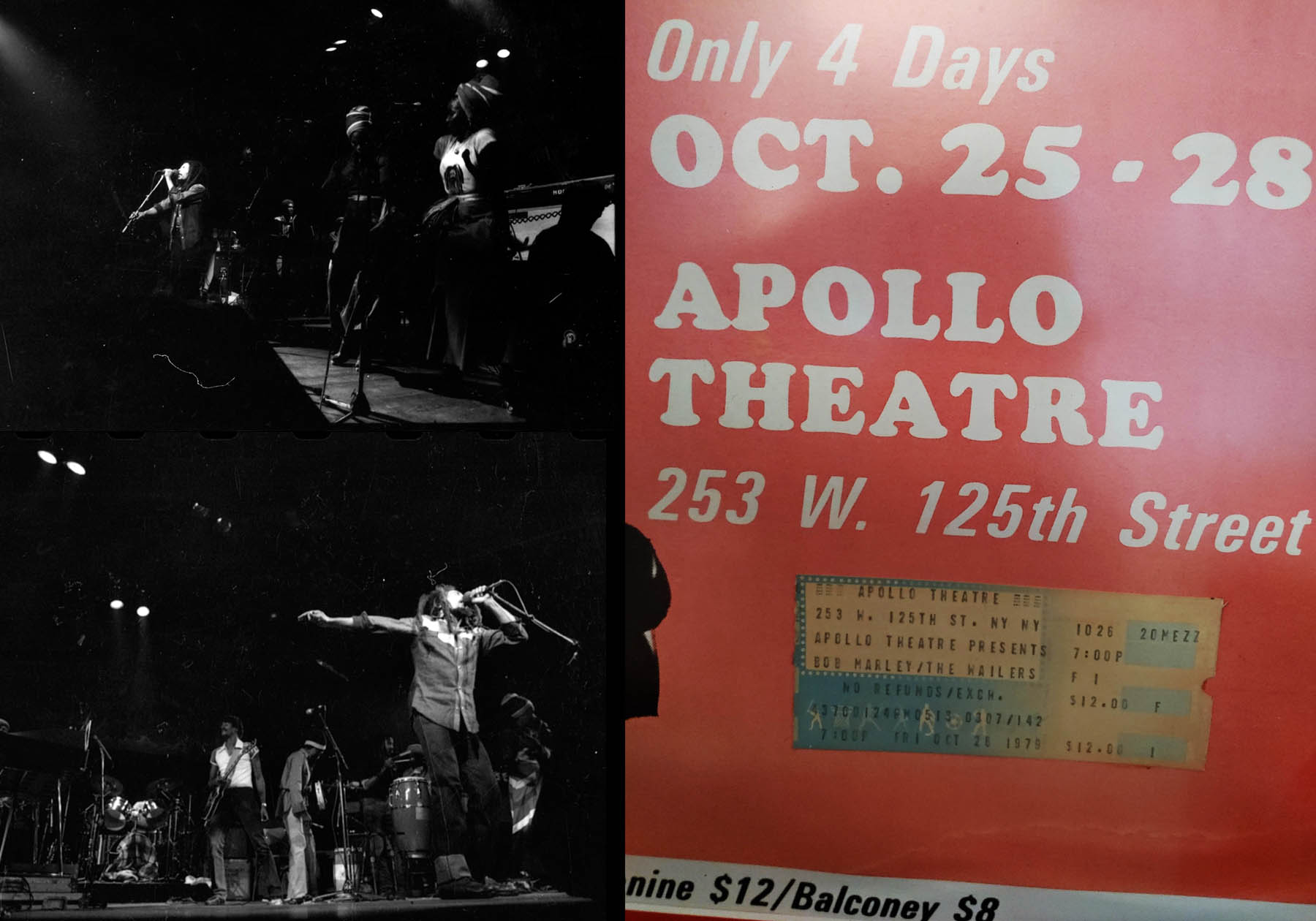

1979

Bob brings reggae to countries that have never heard it live before, including Japan, New Zealand and Australia. His new album “Survival” is greeted enthusiastically as a return to his most militant roots. He plays a benefit at Harvard Stadium in Boston to raise funds for African freedom fighters, and makes three powerful speeches about recognizing Rasta as God Almighty, legalizing herb, and uniting humanity for common purpose. His performance that day is recognized as one of the strongest of his life, and parts of his impromptu declarations are later incorporated into his evocative ballad “Redemption Song.” But those around him sense a permanent weariness and fatigue, his face becoming drawn and lined with pain.

1980

Bob is invited by the King of Gabon to perform in Libreville in January, one of only two performances Bob ever gave in Africa. The second is historic: On April 17, Bob headlines the independence celebrations in Zimbabwe, spending more than $250,000 of his own funds to bring his group there. That summer, he tours Europe with a tumultuously successful review based on his new album “Uprising.” He plays to over 100,000 people in Milan, in a soccer stadium where the Pope had appeared the week before. Bob outdraws the Pope. In September he begins the American part of the world tour as opening act for the Commodores for two sold-out nights in Madison Square Garden, anxious to reach the African-American audience which has always eluded him. The following day, Bob collapses in Central Park while jogging with Danny Sims and “Skill” Cole. Doctors tell him the melanoma cancer has spread to his lungs and brain, and say that he has but weeks to live. Nevertheless, he flies to Pittsburgh and performs his final concert at the Stanley Theatre on September 23, then returns to NY for treatment. Doctors there give up at the end of October. Desperate, he turns to an ex-SS Nazi doctor named Josef Issels in Bavaria, and flies to his Bavarian clinic as the year ends.

” “

1981

Dr. Issels keeps Bob alive for several months, but at the beginning of May he tells Bob there is no more hope. Bob leaves for Jamaica, but makes it only as far as Miami, where his mother lives. On Monday morning, May 11, Bob dies in the company of his family. His final words to son Ziggy are “Money can’t buy life.” Jamaica goes into a state of shock: even Parliament recesses for the next ten days. On May 21 a state funeral is held with Edward Seaga, newly elected Prime Minister, ironically delivering Bob’s eulogy. The biggest crowd in Caribbean history watches as Bob’s body is driven home to his birthplace in Nine Mile, St. Ann. Seaga issues seven postage stamps in his honor, and raises a statue to his memory. His headquarters at 56 Hope Road is turned into the Bob Marley Museum.

|